Ramification

We are familiar with the idea of ramification from botany: in the case of the tree, aboveground elements like limbs and twigs visibly branch out in order to enlarge the overall leaf surface and thereby maximize processes of photosynthesis. The principle of ramification can also be seen in the realm of larger systems: for example, in the case of a watershed, where small tributaries flow into ever-larger rivers before reaching the sea. Ramifications can cover larger areas without eliminating, or pushing out, what is already there, and can thereby connect otherwise isolated entities. And ramification is also a conceptual tool that offers insight— not only into the anatomy of a plant but also onto connections within and between landscapes. This publication presents the innovative perspectives of a select group of landscape architects, urbanists, and biologists whose practices share a forward-looking understanding of their disciplines and who have—knowingly or unknowingly—adopt- ed the metaphor of ramification to think about landscape and make it possible, thereby, to design more sensitively and with a greater orientation toward the future.

With contributions by Céline Baumann, Jana Crepon, Julie Delnon, Georges Descombes, Hilar Stadler, and Paola Viganò. Projects by Altitude 35, Paris; Inside Outside, Amsterdam; StudioPaolaViganò, Brussels and Milan; Superpositions, Geneva; Sylvie Viollier and Cyril Verrier, Geneva; and mavo Landschaften, Zurich.

You can find the book in the following bookstores: Geneva: Fahrenheit 451, Large/Kiosk; Kriens: Museum im Bellpark; Lausanne: Basta!, Payot; Zurich: Hochparterre Bücher, Never Stop Reading; Berlin proqm

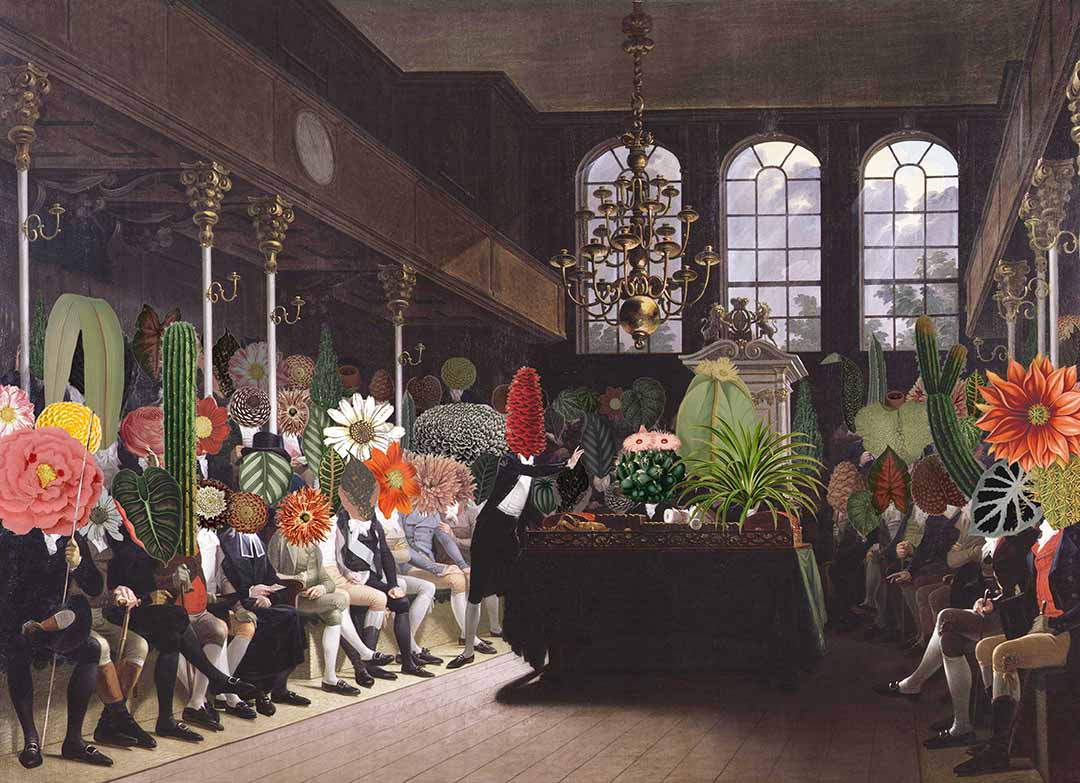

“Human Habitats Need to Accommodate Other Living Beings.”

Landscape architect Céline Baumann designs urban environments,

but she also maintains a prolific practice as an artist and educator. Her Basel-based studio is committed to research on plant life and interrelations with humans. Her intersectional lens in turn informs her design work, in which she aims to create dynamic open spaces that respect the ecology of both humans and nature.

Interview by Viviane Stappmanns.